You never forget your first French predreadnought. Ungainly, unshapely and apparently built with the hull upside down, their aesthetic is best described as uniquely awful. And yet there’s something compelling about something so… so… something.

But what actually is a predreadnought, and why are the French ones so different?

In the late 1880s the French naval establishment received a nasty shock. For nearly 20 years naval thinking had been dominated by the Jeune École – essentially a group of theorists who argued that new technologies meant that the Royal Navy could, if not actually be defeated, at least be threatened with enough of a bloody headache to keep them quiet. A torpedo up the jackstaff tends to ruin anybody’s day, and could be carried on much smaller, cheaper vessels than a battleship.

Behind a swarm of relatively fast torpedo boats, the Jeune École imagined a far lower number of small battleships designed for coastal defence to add to the pain, whilst fast, long-ranged cruisers would lead the British a merry dance across the high seas. And if part of this sounds familiar to a later German plan, you probably wouldn’t be far wrong.

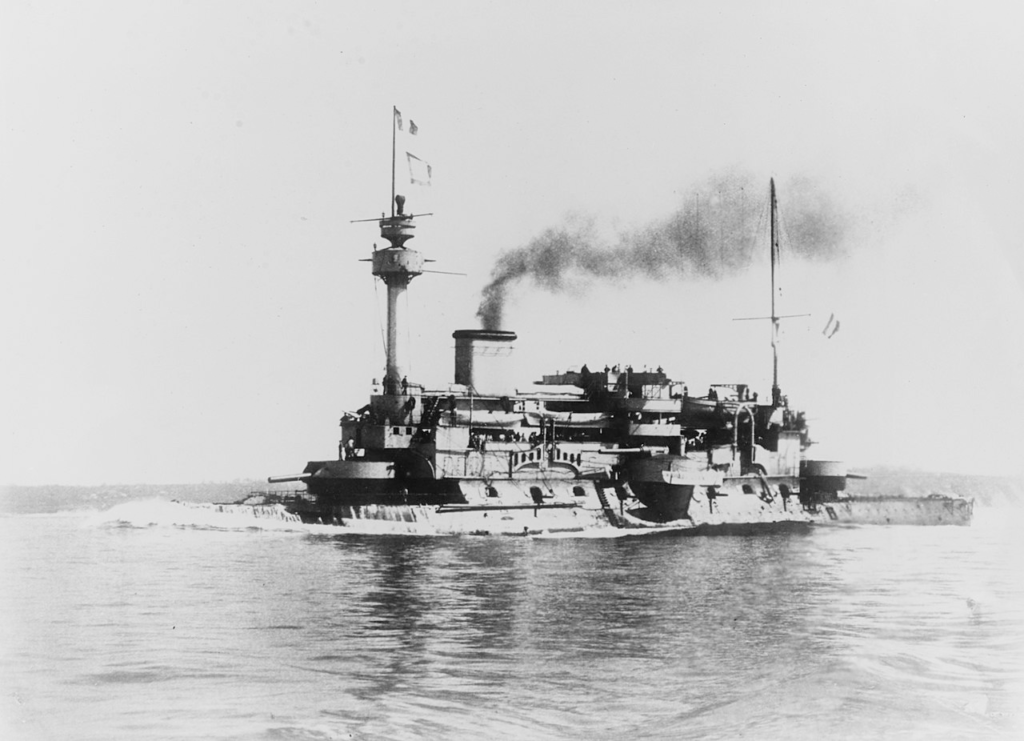

Some of the appeal of this thinking was that it was a lot cheaper than just building massive battleships. Indeed, something of the economics can be grasped by looking at that image of Hoche above.

It’s a truism that every battleship is a compromise. That’s usually taken to mean a compromise between armament, speed and armour. In the case of Hoche it was a compromise between building some sort of battleship or not building one at all.

This cosy state of affairs was rudely interrupted by the British announcement that they were about to build 8 Royal Sovereigns. I mean, not literally – even the Royal Navy’s naming conventions aren’t mad enough to give 8 ships the same name – but a unified class of eight powerful warships specifically designed to kick the arse of anything they met. And explicitly that arse was French: Hoche there would be mincemeat.

Reluctantly the French concluded they would have to meet the challenge.

Now here’s a thing. All these ships we’re talking about are predreadnoughts. The definitions are fairly loose, but broadly speaking they’re made of and armoured with steel – which handily distinguishes them from earlier ironclads. And HMS Dreadnought, launched in 1906, would render them obsolescent: hence the ‘pre’, and it should be fairly obvious to anyone who understands the arrow of time that we only started calling them predreadnoughts in retrospect. So that’s the what. How about the why?

The French response to the Royal Navy’s expansion was to resume building battleships that could nominally go toe to toe with their rivals from across the Channel. Now a normal navy would appoint a competent designer, agree their most conventional design, and build shitloads of those. That’s basically what the Royal Navy were doing, after all.

The Marine Nationale were not a normal navy.

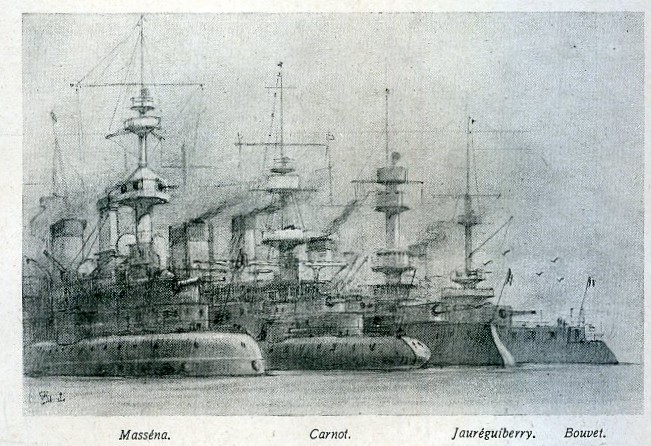

A competition was held to find the least mad design. And four, later five, ships – all from different yards and with different specifications – from this competition were hastily approved. It’s like a Blue Peter competition with added 12-inch guns. And it’s this flotte d’échantillons (literally ‘fleet of samples’ – there’s nothing enchanting about them) that you probably think of as the stereotypical French predreadnoughts.

There’s two things with these ships that catch the modern eye. The first of them is the sheer amount of stuff that’s piled on top of them. That’s not actually unique to the French – battleships of the period were simply loaded up with extra guns, jibs, boats and anything else that threatened to be useful. To modern eyes, raised on a diet of boring grey boxes that seem to prioritise ease of rendering and a reduced polygon count, they’re fantastically busy.

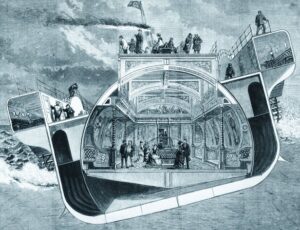

The other thing, and there’s no way around this, is the tumblehome. For the uninitiated, that’s the way the hull curls inwards above the waterline – and the reason these ships look like they carried on building despite it capsizing halfway through construction.

People spend a lot of time arguing about the French fondness for tumblehome, and the fact is that they’re all correct to some degree. It does give the wing turrets a wider field of fire. And it does make boarding actions – as unlikely as the prospect seems in the era of the Maxim gun – difficult. And, yes, it does also serve to reduce the top weight. It’s probably the latter that really drove its continued use.

Because other than the fact this was the house style, one way of forcing the French navy to economise on costs was to limit the displacement of the ships. Cutting the freeboard and building a narrower superstructure saved some vital mass that could instead be invested in the bits that went bang.

Fair enough, I suppose.

That tumblehome proved to be a weakness. Coupled with a longitudinal bulkhead to limit flooding it all but ensured a ship would roll over as soon as it took any water on, and in the Dardenelles that unfortunate fact killed over 600 men aboard Bouvet. It’s important though to realise that it wasn’t entirely without merit, and if the theory had proved sound we’d view it today as perfectly normal.

But, you know… it didn’t. C’est la vie.

10 thoughts on “The enduring beauty of French predreadnoughts”

Comments are closed.

The image of Hoche – the captain’s ordered diving planes down 10, flood the main ballast, flood the negative?

Just have a look at the differing length of the Wikipedia summaries of tumblehome and flare and you’ll appreciate the glorious nature of the former

Review by Wikipedia article length is definitely underrated as a quick assessment of notability!

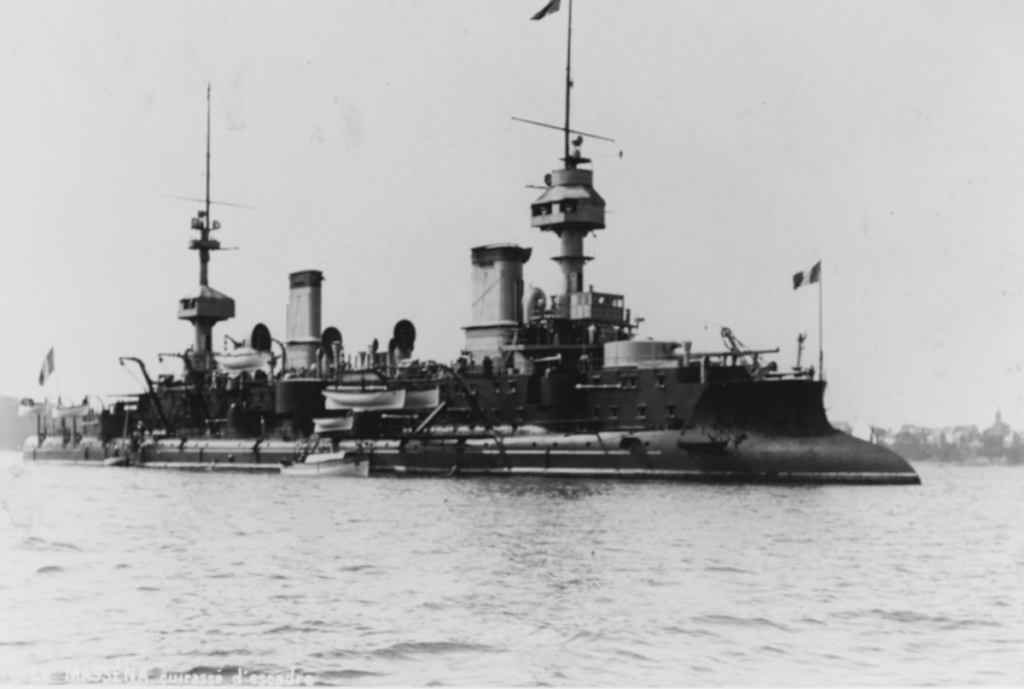

I have to admit that that image of “Jauréguiberry” makes her look menacing and purposeful; even a broken clock is right twice a day.

I adore predreadnoughts, but I also love ugly dogs and blue cheese.

If you’ll forgive a little bragging, just restored an image of a pre-dreadnaught French battleship for Wikipedia. One of the saner ones, alas.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:French_Battleship_Justice_by_the_Detroit_Publishing_Co,_1909.jpg

Also, the models of the ships are just… wow.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53206658r.r=Jaur%C3%A9guiberry.?rk=64378;0

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Model_of_the_French_cruiser_Duguay-Trouin_(1877)_-_Original.jpg

They show what’s below the waterline, and it looks so very wrong.

These are apparently so hot they got held for moderation 😀

Or possibly offensive in other ways – it’s hard to be sure…

I can never remember the Jiggleberry’s name but that bottom photo does look rather menacing!

All these ships look very wrong, whatever the angle you look at them. I guess it’s kind of an achievement in itself ! But then, at the same time, as I’m French and very biased, I can’t help thinking they also look threatening and dangerous. 🙂