The general trend of naval warfare has – loosely speaking – been one of putting holes in your enemy from ever longer distances. From the race-built galleons of the 16th century to the aircraft carrier of today, the range over which conflicts were intended to be fought have increased exponentially. It therefore comes as a slight surprise to find people suddenly sticking rams on everything from the 1860s onwards. Pointy ships had gone extinct with the Romans. What the heck was going on?

The first stirrings of the renewed vogue for rams, almost inevitably, began with the French. Always dangerously close to having an idea, at some point it occurred to them that contemporary armour was rapidly outstripping the ability of the weapons they had to penetrate it. The obvious solution to this was to hit the enemy with something bigger, and what could be bigger than your own ship?

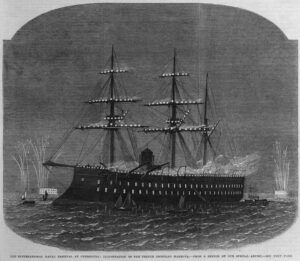

Arguing that steamships could sail in any direction to the wind, and could therefore strike the enemy wherever they damn well felt like it, in 1859 Henri Dupuy de Lôme took inspiration from the past and designed the ironclad Magenta with a ram bow. The game was now afoot.

And in particular it was afoot on the other side of the Atlantic. Facing exactly the same problems, and following exactly the same logic, both sides in the American Civil War embraced the path of the forceful prod. The success of Virginia in sinking wooden warships, albeit with some damage to itself, seemed to validate the general concept.

The specific concept of Virginia on the other hand was less successful. Attempting to stick your nose into other ships whilst blessed with a turning circle of a couple of miles was always going to be hit and miss. And mostly miss.

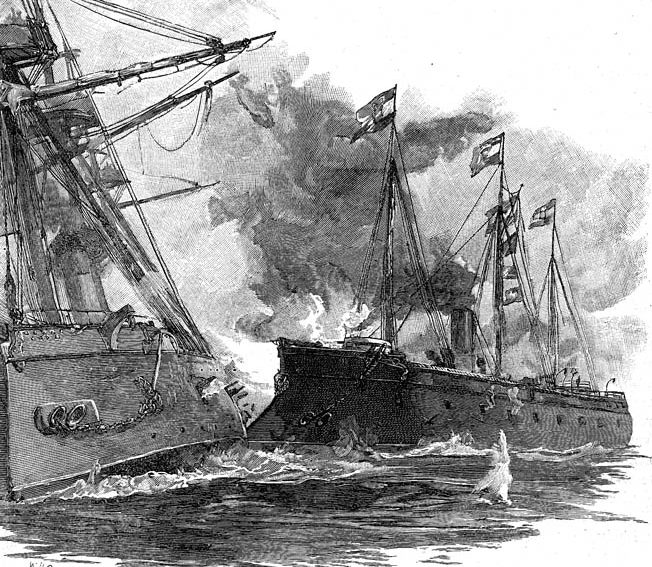

With the Americans proving that poking great big holes into vessels was still militarily useful, further validation soon arrived from the Battle of Lissa. One of the least competent naval battles ever fought, the skirmish between Italy and Austria saw multiple ramming attacks. Amongst the rare successful ones was the sinking of ironclad Re d’Italia. Suddenly everybody was all about the ram.

However a slightly more sober review of Lissa would have revealed a more nuanced picture. For one thing, actually landing a blow required a combination of skill, luck, and a spectacularly stupid opponent. With the increased professionalism of the world’s navies, or simply Darwinian selection, the last of these was likely to be in short supply. Ships attempting to ram also received an impressive amount of damage. Nonetheless, the ram was now de rigeur for every well-dressed warship.

And now began a reign of error.

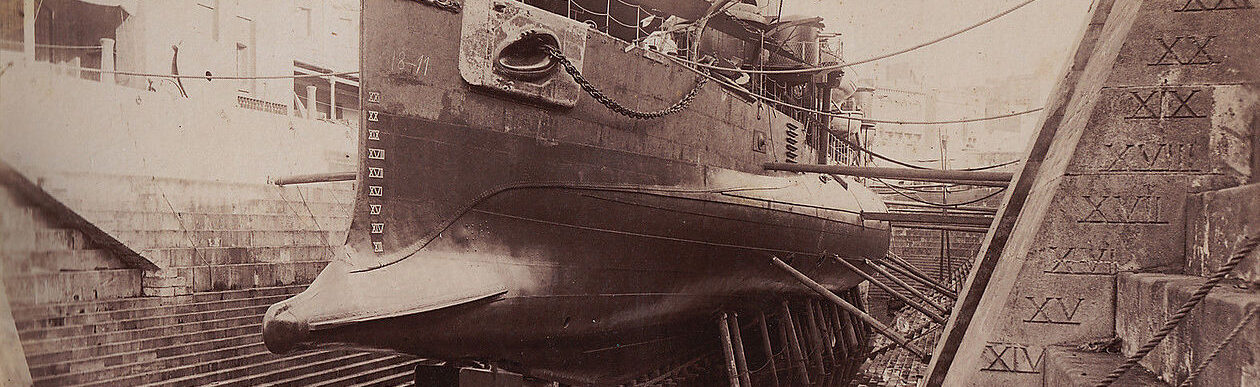

See, it turns out that the easiest ships to ram are those closest to you. And the closest ships to you are usually your pals. And it turns out that pals often hit each other by accident. A host of shipwrecks – from Grosser Kurfürst to Victoria – bear witness to the ram’s awesome power to make a bad situation worse. Many otherwise survivable collisions served to persuade navies that the ram was deadly. They just forgot to ask who it was deadly to.

Despite this, the concept was remarkably long-lived. Partly this was because it improved the line of many hulls, lengthening the waterline with little increase in weight. This made it essentially a free action even if it was unlikely to ever see use offensively. It’s also why a vestigial unreinforced ram appears quite late into the dreadnought era. The ram concept might be ironically pointless, but it’s still a good shape.

It’s also important to note that nobody* was – quite – mad enough to design a ship that only had a ram for offence. Maybe it was a lingering fondness for things that go bang. Maybe there was the nagging feeling that armour wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. Either way, the ram usually had a serious set of guns following it, even when it was explicitly the main weapon.

That didn’t stop people being daft, of course. At one point the British unwisely left a boffin alone with some crayons, and after eating most of them he devised the idea of the torpedo ram.

The torpedo ram consisted of two ideas of varying quality. The good idea was sticking a hole in your enemy with a torpedo. The bad idea was to then insert yourself in the hole. The point of this was never satisfactorily answered, but the name “torpedo ram” sounded like just the sort of thing with which to fight passing Martians. HG Wells duly took the hint, although the resulting vessel had little to do with HMS Polyphemus. Despite the threat of the red planet the Admiralty never built a second.

The ram eventually passed into history for a second time. It slowly dawned on everybody that gunnery had regained the ascendancy and that sinking your own ships was of limited utility. The trend towards fighting at longer ranges resumed.

There’s one final irony to the ram story, however. The loss of Admiral Tryon in 1893 arguably owed a huge amount to the dangers of equipping warships with dangerous pointy bits and asking them to move about in close proximity. His loss was a massive blow to the Royal Navy at a critical moment in its development.

And seen from that viewpoint, Dupuy de Lôme did more to mess with the Royal Navy than any other Frenchman before or since. So maybe the ram was a success after all…

* Correction: beyond the short-lived American experiment with the US Ram Fleet, that is. In retrospect it’s weird that the world’s foremost gun fetishists would have gone without.

5 thoughts on “Getting to the point”

Comments are closed.

“Boopable Snoots” tag FTW

Seconded.

The existence of this tag implies – nay, teases – loads more fun at the expense of last quarter of the 19th century warships.

Surprised you didn’t mention the Anson sinking the Utopia whilst she was anchored and stationary. To be fair it was a case of passive ramming.

It is interesting that nearly all of the successful sinkings by Ram were due to bad ship handling.

Search the Bélier-class ram boat on Wikipedia. You’ll be surprised. From the French of course