Growing up in the Anglosphere, it’s easy to assume that celebrating futile and needless defeat is a peculiarly British characteristic. After all, in the national imagination Dunkirk was a noble victory. Robert Falcon Scott was the bravest little ice cube in Antarctica. The commissioning of Mrs Brown’s Boys the cultural highlight of- well, okay. There are limits.

For embracing sheer unrelenting misery as a national characteristic, however, one nation stands supreme: Russia. They’d love Mrs Brown’s Boys. They might even think of it as a comedy…

And nothing, perhaps, captures this tendency quite as well as the story of the protected cruiser Varyag. Who could resist a rousing patriotic battlesong that says – loosely – “we’re all screwed”. Or in the slightly longer translation –

Get up, you comrades, everyone to his place, the final parade is at hand.

Our proud “Varyag” will not surrender to the enemy. No one wants mercy.

I dunno about you, but if I were aboard Varyag I’d have a few questions there. Run me past that “mercy” bit again, could you? I’m sure we could take just a little bit of mercy? Just a taste? No? Suit yourself – I’ll be in the lifeboat.

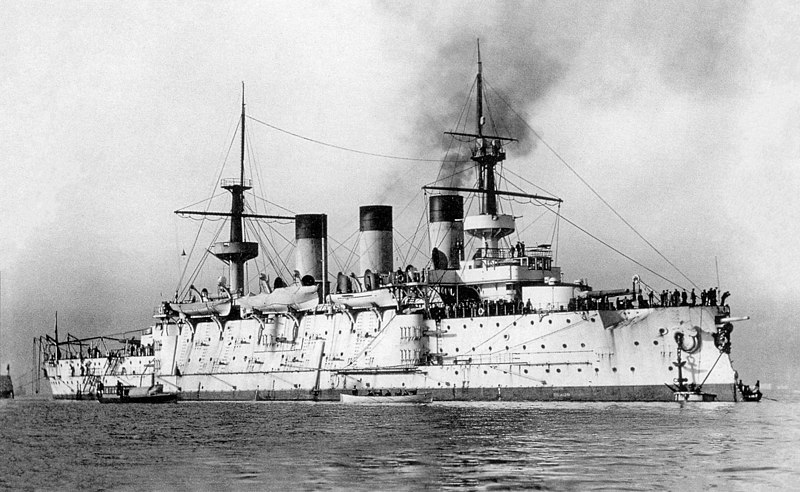

The Varyag story starts, unexpectedly, in Philadelphia. In 1898 the yard of William Cramp and Sons laid down the cruiser’s keel and began construction of hull 301. You might reasonably ask why Russia was forced to place orders for warships in America. The reason was that the Russian yards were already fully occupied with building battleships. And if you know anything about Russian battleships of the period, you might reasonably conclude that their yards might as well not have bothered.

In contrast Varyag, with its twelve six inch guns and 23 knot top speed, was a perfectly competent light cruiser. It had the range necessary to the role, the armour was decent, and unlike the battleships it didn’t make friendly nations recoil in horror when it arrived in their harbours.

However cruisers are also supposed to impress one’s enemies and on this score things were less good. Because on completion Varyag was sent to the Pacific, where with unfortunate timing a nascent Japanese navy was just about to start throwing its weight – and rather a lot of ordnance – around.

Now most people have their favourite tales from the Russo-Japanese War. For fans of badly fought naval battles – and disastrous voyages that even Coleridge might have thought a bit much – it surely stands alone. But even in these annals of incompetence the battle of Chemulpo stands tall.

The battle itself was opened by the Russian gunship Korietz. Bustling out of Chemulpo to fetch orders from Port Arthur, it stumbled across the Japanese cruiser Chiyoda, mistook it for a Russian ship*, loaded its guns for a salute, and then accidentally discharged them straight at the Japanese. Chiyoda replied to this idiosyncratic performance with equal enthusiasm, and fired off a torpedo or two to jolly things along. Honour satisfied, and with neither side actually doing anything as unmannered as hitting anything, Korietz then retreated.

It’s unclear when Varyag’s captain, Vsevolod Rudnev, first realised things were more serious than a bit of light-hearted torpedo-firing in the harbour approaches. If Korietz’s experience made no sense, then Japanese Rear Admiral Uryū Sotokichi rocking up with half a dozen more cruisers should have provided some clarity. Uryū asking neutral ships to move out of the way so he could blow the heck out of the anchored Varyag should definitely have rung an alarm bell. Uryū casually unloading an entire army division right next to the Russian ships should have rung whole belfries of them.

Rudnev watched all this without doing anything and then called a conference amongst the neutral warships – including British, French, Italian and American representatives – to ask if the Japanese openly declaring war on him possibly meant anything? That’s the thing about sangfroid. Very little of it flows into the brain.

The other nations agreed that yes, the declaration of war possibly did mean something was afoot. Would Rudnev please surrender quietly for the good of everybody’s paintwork?

Rudnev might not have been a quick thinker, but he was incredibly brave. Or possibly just incredibly thick. Resolving to fight his way out, the Russian ships weighed anchor, sailed out of the harbour and opened fire on the Japanese. Almost immediately Rudnev was hit on the head. The effects of this blow are readily apparent by his sudden and uncharacteristic outbreak of cognitive function – ie running straight back into port to ask everyone to explain about that surrendering thing again.

Giving up didn’t mean surrendering the ships, however. First to go was Korietz, in an explosion that had all the other ships hurriedly explaining again about their desire to not open tins of paint. Did he happen to know what opening the seacocks did? Rudnev revealed he – or at least his engineers – understood the finer points of scuttling a ship without blowing everyone else to kingdom come. Varyag slipped beneath the waves in a non-explosive manner. And that – apart from a Japanese honour accorded to Rudnev for insanity in the face of overwhelming force – should have been the end of that. Except it wasn’t…

At the end of the war, Japan fished Varyag out of the water, renamed it Soya, and commissioned it once again as a cruiser, albeit one used mostly for training duties. You can imagine the syllabus now. “Take a good look at the holes in that. Put them in an enemy ship. Try not to take too many into your own.” It regularly rocked up in Hawaii, and it’s tempting to suggest at least some of the young officers were taking careful notes. You never knew when you might be back. And it’s easier to take notes when somebody isn’t shooting at you.

By Varyag’s standards this was positively sedate. Nobody did anything nasty to it for virtually a whole decade. Certainly not the Japanese. It even had a nice paint job.

Meanwhile their former enemies were broke, suffering a shortage of ships and, with the outbreak of the first world war, on the same side. The Russians cautiously asked if the Japanese had any spare ships to sell, and the Japanese conceded that they might. They hadn’t even taken the Cyrillic writing off some of them…

Back in Russian hands, Varyag assumed its former identity. If nothing else they were proud of its fighting spirit. The fact that the Japanese bizarrely hadn’t actually taken the name off the stern also saved them a job. Unfortunately it needed a refit before being returned to service and was duly sent to Liverpool in 1917.

At this point things went wrong again.

Seamen aboard Varyag reacted to the October Revolution by raising the red flag. If this was viewed with distaste by the blue half of Liverpool, the British government were even less impressed. Varyag was promptly confiscated. It takes some effort to lose the same ship twice, but Russian politics had somehow achieved it.

And when the Soviet government declined to buy (and presumably then lose) Varyag a third time the ship’s fate was sealed. It was initially handed to a non-plussed Royal Navy. The navy then mothballed it until nobody was looking, and in 1920 flogged it to a German scrapyard. The Germans never did anything naughty with ships. Long history of not having wars with Britain. Literally months, by this point. Ages. Nothing could possibly go wrong.

Yeah, right. Varyag broke its tow and involuntarily went the full Moskva within sight of Ailsa Craig. Bits of it are still there now, though most was salvaged.

![Postcard captioned "Destruction of the Russian cruisers [sic] Varyag and Korietz in the harbour of Chemulpo"](https://dreadships.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Battle_of_Chemulpo.jpg)

All of which is why, on the long haul down the Firth of Clyde, you come across a curious memorial by the roadside marking the last resting place of one of history’s more storied vessels. A cross stands tall, and nearby a metal tablet tells the story of a ship that was owned by six nations (the USA when being built, Imperial Russia, Japan, the Bolsheviks, Britain, and finally – briefly – Germany). A ship whose history is inspiring and comedic in equal value, and comes with its own theme tune. And a ship that apparently always fancied a fight, even at the end.

There was one more act in the Varyag story. Because when the Russians purchased it back, Japan rather blotted their copybook as allies by refusing to return its flag. And after the second world war that flag found its way to Korea, who then – in 2010 – finally returned it to Russia as a gesture to mark twenty years of diplomatic relations. Technically however the flag is only on a short term loan and the Republic of Korea can theoretically ask for it back at any time. And given Varyag’s history, as well as the more recent performance of the Russian navy, who would bet against the Russians managing to lose it yet again?

*this is particularly baffling as Chiyoda had been anchored with the Russians at Chemulpo for the previous ten months. That’s simply spectacular levels of inattention, even by Russian naval standards

7 thoughts on “Varyag degrees of success”

Comments are closed.

Looking forward to more posts tagged “Give up the ship just a little bit”

I laughed, I cried, I admired your luminous descriptive passages.

Beautifully written, thanks

I learnt such a lot about curling from this.

The Russo-Japanese war highlights so much wrong with the Russian Empire at the time.

There’s an Orthodox church in the Philadelphia neighborhood near the site of Cramp’s yard, with a memorial to the Varyag.

Every few years, the Inquirer will do a story on this bit of local history.

I needed a laugh this morning and this article delivered along with a healthy dose of education. Vsat, keep it up.